Introducing the new Blancpain Grande Double Sonnerie — the brand’s most complex watch to date and a true pinnacle of mechanical watchmaking. Full story below.

At the Farmhouse—the place where Blancpain’s most exceptional creations come to life—we were greeted by a large, cheerful group from the brand, their faces lit with big smiles and an unmistakable spark of excitement in their eyes. Among them was Marc A. Hayek, Blancpain’s President & CEO, welcoming us personally. With every minute, the anticipation for the day ahead kept building. More precisely, the anticipation of finally seeing the watch we had come all the way to Le Brassus for.

A week before the trip, I had received the press release for the new piece—without any images. Cruel, yet brilliant. I spent the entire week imagining how the watch might look. I reread the text several times, trying to picture where each complication would sit, how it would all come together. Autumn landscapes of the Vallée de Joux flashed past the window of the Mercedes minivan. The final hill before Le Brassus revealed that magical view of the small but historically charged village. And still, the thought of what these mysterious new Blancpain watches looked like never left my mind.

It was clear from the start that this launch was a big deal for Blancpain. The energy in the room, the pride, the desire to finally show what the team had been developing for eight long years—completely understandable. Because this wasn’t just another complication. This was something the watch industry had simply never seen before. A romantic, emotional, and technically staggering achievement.

The most complicated watch in Blancpain’s history.

Meet the Blancpain Grande Double Sonnerie—a two-melody grande sonnerie, petite sonnerie, and minute repeater, combined with a flying tourbillon and a retrograde perpetual calendar.

But before we could finally see the watch itself, we were lucky enough to witness how it was created—to hear its story, understand its mechanics, and meet the people who brought this extraordinary piece to life.

Eight years ago Marc A. Hayek conceived the new grand complication project with the ambition to create a grande sonnerie that would truly advance the art of watchmaking. The idea was to move from merely sounding the time to doing so with a complex and beautifully constructed melody.

Although it is standard to chime the time using just two notes, he pushed Blancpain’s watchmakers to develop a grande sonnerie equipped with four notes. More than that—and greatly increasing complexity—he wanted these notes to form an actual melody. Then came the inspiration: why not sound time with two different melodies, both played on four notes? The classic Westminster chime, and an original composition penned by rock star Eric Singer of KISS. And why not allow the wearer to switch between them with a single push of a button on the case?

On top of all this, the new Grande Sonnerie had to be a watch the owner could comfortably wear—not a technical exercise destined to stay hidden in a safe. That was the daunting task handed to Blancpain’s movement designers.

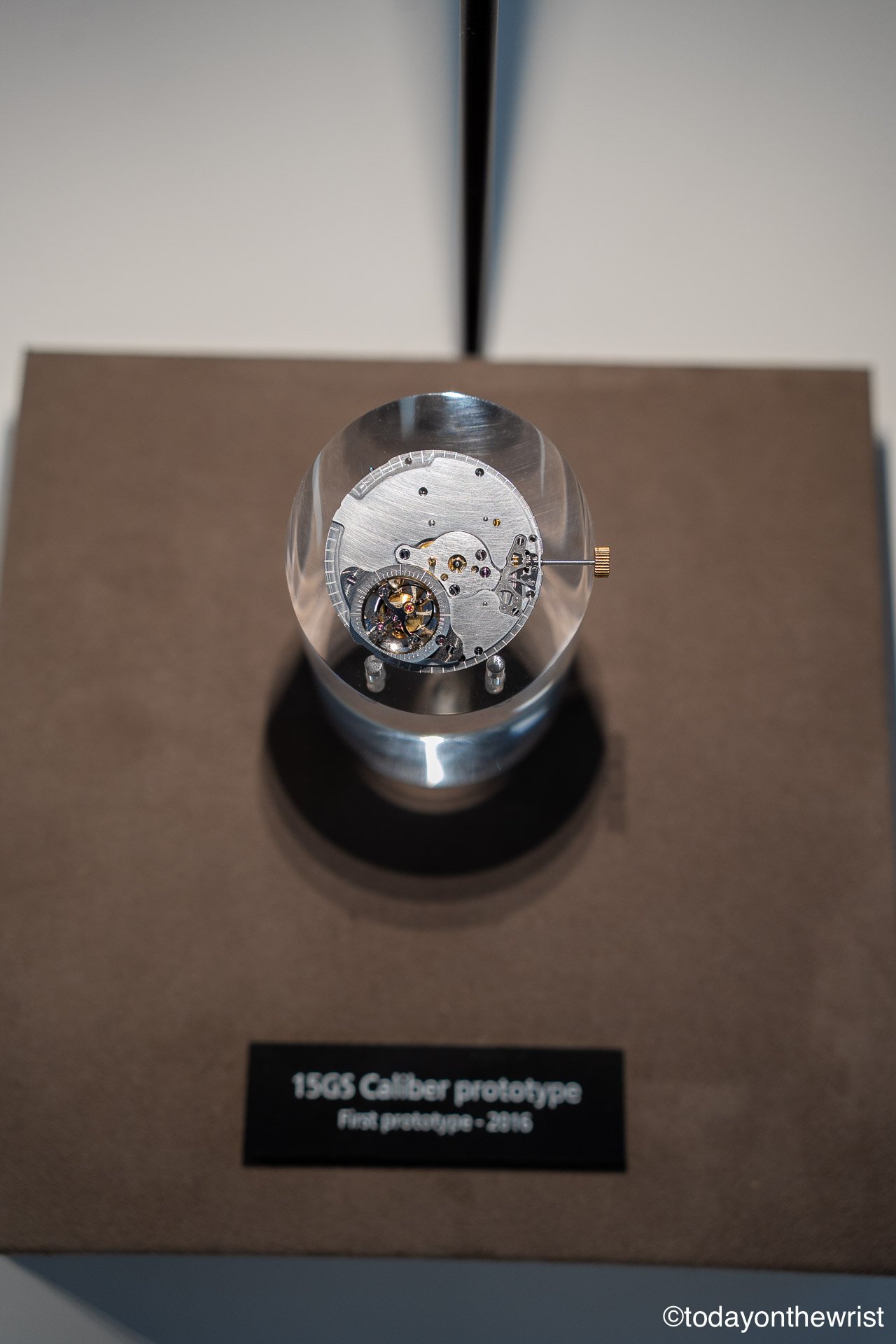

Eight years later, the four-person team, led by Marc A. Hayek, stands in front of my camera with the finished watch. Each of them speaks with incredible pride about how all of this became possible. 1,200 technical drawings, 21 patents developed during the project (13 incorporated into the final movement), 1,053 components inside the calibre out of a total of 1,116—all entirely designed, produced, assembled, and decorated in-house.

In that moment, you understand the extraordinary things people can achieve, and how lucky I was to be in the place where all of this came to life, surrounded by these brilliant minds. This is not just a new watch—it is an important moment for the entire world of horology.

Sounding of time with a melody

Traditional grande sonneries rely on a simple two-tone chime, but Blancpain’s Grande Double Sonnerie goes far further by creating a true four-note melody using E, G, F, and B. This instantly doubles the mechanical complexity, requiring four independent hammers and gongs, each precisely tuned using laser measurements so all notes harmonize perfectly.

Tempo is equally crucial. The human ear detects irregularities of just a tenth of a second, which is why Blancpain developed a patented silent magnetic regulator that keeps the rhythm impeccably stable without adding any distracting mechanical noise. To refine the melody even further, the intervals between notes are scientifically measured, and watchmakers make micron-level adjustments to the mechanism.

Unlike conventional grande sonneries, Blancpain plays the full melody on the hour—hours followed by all four quarters. To achieve the best acoustic quality and volume, the movement uses gold sounding rings and a gold acoustic membrane hidden within the bezel, chosen after extensive testing for their superior resonance. The result is a chiming watch engineered not just to tell time, but to perform a genuine musical composition.

Alongside the chiming complication, the movement also features two additional grande complications. The flying tourbillon—already an emblem of the house—now operates at 4 Hz instead of 3 Hz, with a silicon balance spring that resists magnetism and improves chronometric performance through lighter weight, ideal geometry, and more consistent amplitude as mainspring torque changes. Beyond its technical prowess, the tourbillon’s finishing is a spectacle in itself: the mirror-polished cage creates a mesmerizing play of light as it rotates.

The second is the Retrograde Perpetual Calendar. Developing the Grande Double Sonnerie required a completely new construction of the calendar—one rarely, if ever, seen in the world of grand complications. Typically, perpetual calendars are built as modules on a separate plate. But such a module would obstruct the open architecture of the Grande Double Sonnerie, hiding much of the sonnerie mechanism. Blancpain instead took the far more demanding route of fully integrating the calendar into the movement.

The date is displayed along the left perimeter of the movement, while the day, month, and leap year appear on two subdials on the right. Normally, Blancpain’s patented under-lug correctors are integrated into the case—allowing adjustments with a fingertip and no tools—but here, the fully integrated movement construction dictated a different approach.

This single, module-free architecture also helps keep the watch relatively slim and wearable. The case measures 47 mm in diameter, 14.5 mm in thickness, and 54.6 mm lug-to-lug, with 10 m of water resistance. It is available in either red or white gold.

Inside is the manually wound, bidirectional-winding Caliber 15GSQ, offering a 96-hour power reserve and 12 hours of striking autonomy in Grande Sonnerie mode. Operating at 4 Hz, the movement measures 35.8 × 8.5 mm and consists of 1,053 components (out of a total of 1,116 for the complete watch).

After familiarizing ourselves with all the technical details of the new watch, we headed off to discover how its finishing is created. Blancpain has a dedicated finishing workshop in the same building for its high complications, where skilled craftsmen apply the full range of traditional decorative techniques.

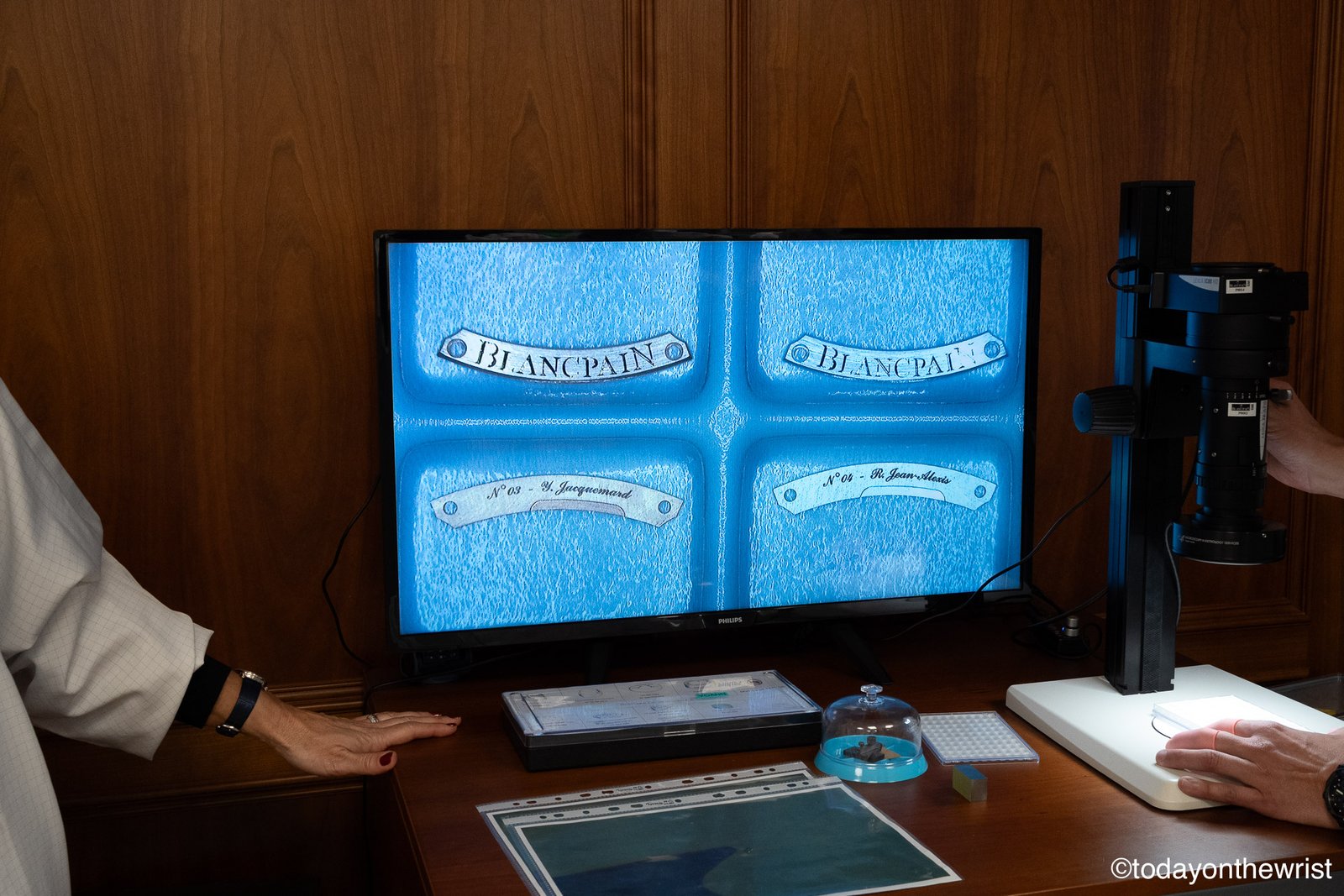

26 bridges and the mainplate are crafted from 18 ct gold, with traditional hand-finishing techniques applied throughout: anglage (including 135 sharp inward angles), perlage, mirror polishing, diamond milling, and straight graining—all executed entirely by hand. Blancpain applies these finishes not only to the visible surfaces seen through the open dial and sapphire case back, but also to the hidden sides that only a watchmaker assembling or servicing the movement would ever see.

A testament to this level of craftsmanship are the 135 crisp interior angles found across the movement. Such bright, sharp angles can only be made through meticulous handwork: first carving the edges, then polishing them with progressively finer abrasives, and finally perfecting them with stems of wild gentian wood sourced from the Vallée de Joux. Knowledgeable collectors know that these interior angles cannot be produced by machines—making them a hallmark of true haute horlogerie.

Blancpain’s Grande Double Sonnerie demanded far more than traditional watchmaking savoir-faire. For Romain and Yoann—two watchmakers with more than a decade of experience in minute repeaters—the project expanded their world far beyond the loupe and workbench. In a repeater, the tones only need to sound pleasant; in a grande sonnerie, pitch must be flawless and the tempo scientifically perfect. And all of this had to be integrated into a single mainplate, with no precedent to follow. They spent more than six months defining the assembly sequence and crafting the specialized tools required for the job. Today, each watch requires nearly a full year of work, assembled entirely from A to Z by one watchmaker, who then engraves his signature on the gold plaque mounted on the movement.

Production is limited to just two timepieces per year, with a price of around €2 million including tax.

It took us half a day to go through all the technical and aesthetic details inside the Blancpain manufacture, and finally came the culminating moment—seeing the Blancpain Grande Double Sonnerie itself. We stood before a black door leading into a small, dark room. Inside, a watchmaker and Marc A. Hayek were waiting, the anticipation of the reveal almost electric. We were the first members of the press in the world to see and hear this watch. The door closed behind us, the lid of a large black presentation box lifted, and there they were—the very watch I had been imagining for so long.

A few seconds later, the chiming began: first one melody, then another, as the watchmaker switched modes. Could this truly be possible? Mechanically? 1,053 microscopic components interacting in perfect harmony, without electronics. It is possible—because people made it possible. Goosebumps. In that moment, I remembered exactly why I love watches. Mechanical watches.

More details at blancpain.com.